Decarbonizing urea production in India via renewable ammonia

By Kevin Rouwenhorst on December 02, 2024

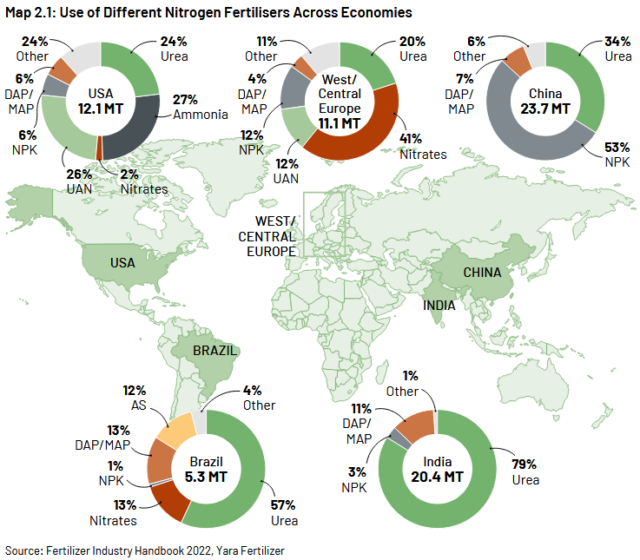

Click to enlarge. Nitrogen fertilizer use by region, with urea dominant in India, Brazil and China. From Green Urea: Economic and Environmental Benefits of a Low-Carbon Future (July 2024).

Around 55% of current global ammonia production is converted to urea (CO(NH2)2), a fertilizer and chemical that requires CO2 and ammonia as feedstocks. Urea is the dominant fertilizer in numerous countries, including agricultural giants Brazil, China and India. Recently, the International Forum for Environment, Sustainability & Technology (iFOREST) published the report Green Urea: Economic and Environmental Benefits of a Low-Carbon Future, detailing a roadmap for the decarbonization of urea production in India. iFOREST is an India-based independent non-profit environmental research and innovation organisation.

Forecast urea usage in India

Urea represents around 79% of nitrogen fertilizers used in India. According to Fertiliser India, around 31.2 million tons of urea is annually produced in India. Over the past few decades, this has been supplemented by around 5 to 10 million tons of urea imports. Simultaneously, India is a current net ammonia importer, with 2.2 million tons imported in 2022 according to the World Bank.

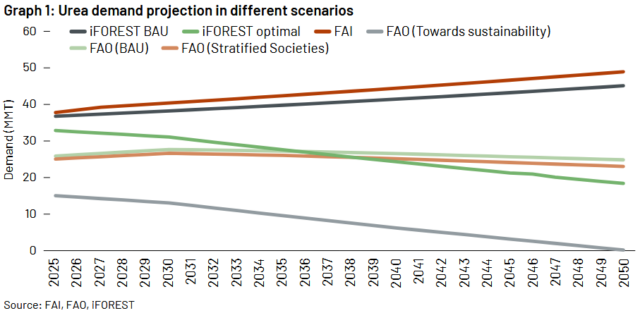

Click to enlarge. Demand projections for urea in India, according to various organizations. From Green Urea: Economic and Environmental Benefits of a Low-Carbon Future (July 2024).

Demand forecasts for urea in India vary widely, with typical business as usual (BAU) scenarios forecasting growth in urea demand, primarily linked to an expected population increase in India. Decarbonization scenarios forecast a decrease in urea demand toward 2050, based on the more efficient use of urea fertilizers.

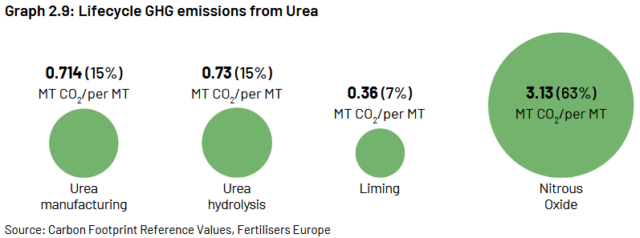

Click to enlarge. Value chain emissions for the urea fertilizer industry (global). From Green Urea: Economic and Environmental Benefits of a Low-Carbon Future (July 2024).

Overuse of urea is a key issue, resulting in a relatively low yield per quantity of applied fertilizer. About 63% CO2 equivalent emission from the urea fertilizer industry occurs during the application step, via the formation of nitrous oxide. National programs exist in India to reduce urea use, and to diversify fertilizer usage.

Decarbonizing urea plants in India

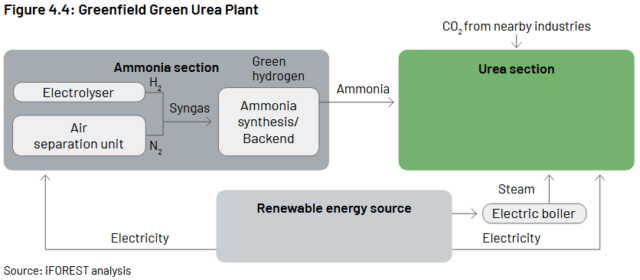

Click to enlarge. Schematic of “green” urea produced with reduced emissions from renewable ammonia and CO2 from nearby industries. From Green Urea: Economic and Environmental Benefits of a Low-Carbon Future (July 2024).

Although the fertilizer usage may eventually be diversified in India, this will not occur instantaneously. Thus, decarbonization of Indian urea production will be required over the coming decades to meet climate goals and reduce agricultural emissions. The key focus of this will be feedstock switching, for both ammonia and CO2.

India is a current net importer of ammonia. However, India has a strong potential for domestic renewable ammonia production via water electrolysis. For example, AM Green recently reached FID on a 1 million tons per year renewable ammonia plant in Kakinada, which is a retrofit of an existing production plant (the Nagarjuna Fertilizers and Chemicals Limited complex). John Cockerill will provide around 1.3 GW of alkaline electrolyzers for the project. AM Green has also ordered 140 MW of John Cockerill electrolyzers to retrofit the National Fertilizers Limited complex in Nangal. The Nangal complex is landlocked, implying the renewable ammonia is not easily transported overseas and will likely be used for domestic purposes. iFOREST (and numerous other organisations) forecast that renewable ammonia production will be a lower cost alternative for low-emission ammonia production in India, compared to gas-based ammonia production combined with CCS (Carbon Capture & Sequestration).

Sourcing CO2 in India

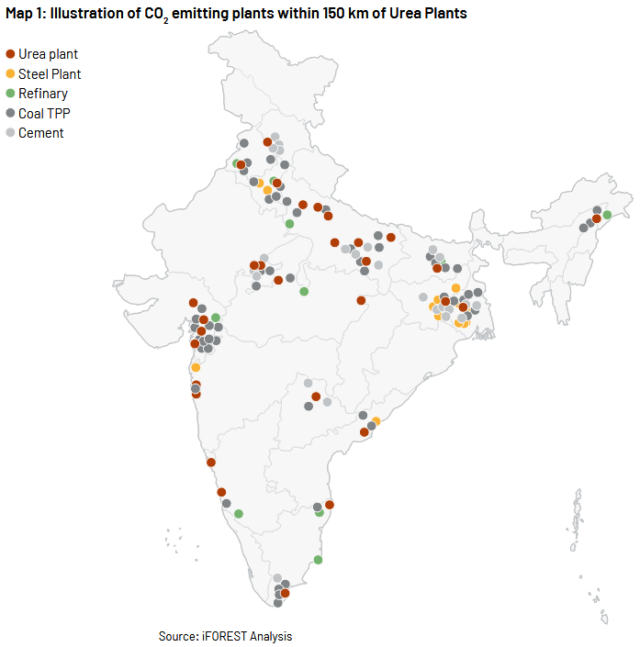

Click to enlarge. Map of CO2 emitting plants within 150 km from urea plants in India, indicating a likely reliable supply for urea production. From Green Urea: Economic and Environmental Benefits of a Low-Carbon Future (July 2024).

CCU (Carbon Capture & Utilization) via sector coupling will be relevant for CO2 sourcing for Indian urea plants. The report of iFOREST highlights various CO2 emitting plants within 150 km from urea plants in India, such as steel plants, refineries, coal-fired power plants, and cement plants. The CO2 will be utilized for a second time for urea production, instead of directly being emitted. This makes the produced urea a transitional product, rather than a low-emission product.

It should be noted that not all of these CO2 sources will be reliably available in the long term. Coal-fired thermal power plants and steel plants can decarbonize directly via renewable electricity, or indirectly via ammonia and hydrogen, eliminating CO2 altogether. However, cement plants will always produce CO2, and some processes in refineries will continue producing CO2, including ethylene oxidation to ethylene oxide. The report estimates that the cement industry offers the lowest cost CO2 capture. Cement production is located within 150 km for many urea plants, making this a potential reliable CO2 source. For example, the fertilizer complex in Nangal has the Gagal Cement Works of Adani Cement at 80 km distance, in Barmana. Significant CO2 transport infrastructure via pipelines will be required to allow for such sector coupling.

In most locations, CCU for urea production will be in competition with existing methanol production. Although India does not currently have a large methanol production base, a few newbuild CO2-to-methanol projects have been announced, with hydrogen to be produced via water electrolysis.