New Coalition Plans to Build Offshore Green Fueling Hubs

By Stephen H. Crolius on June 13, 2019

Last week Wärtsilä, the Finnish engine and energy equipment manufacturer, unveiled a concept for producing and distributing low-carbon maritime fuels from purpose-built facilities in the waters off northern Europe. Dubbed Zero Emission Energy Distribution at Sea (ZEEDS), the initiative is intended to help meet the International Maritime Organization’s target of halving the shipping sector’s carbon dioxide emissions by 2050. And although Wärtsilä’s press release on June 3 mentions only “clean fuels,” the headline used by logistics-sector publisher Freight Week for their June 5 story is “Offshore fuel hubs to supply green ammonia for zero-emission future.”

Wärtsilä is the lead entity in the six-member ZEEDS coalition. Four of the other five are Norwegian: energy company Equinor; offshore engineering and technology company Aker Solutions; engineering, procurement, and construction company Kvaerner; and ocean freight company Grieg Star. The final member is Danish shipping and logistics company DFDS.

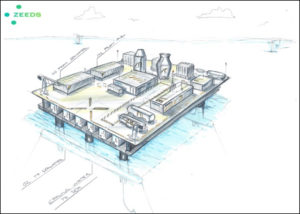

The value chain envisioned by the coalition starts with offshore energy collection. “Clean energy . . . would be supplied by around 75 big wind turbines per hub,” according to a June 6 story by maritime industry publisher Hellenic Shipping News. “Solar and wave technologies are also potentially available in the push to harness energy from the ocean.” The hubs themselves “are designed as gravity-based structures in shallow regions and potentially semi-submersible floaters in deeper water.” Hydrogen and ammonia are the clean fuels that received explicit mention during the unveiling. “Hydrogen production and storage could be accommodated on an under-deck of the installations,” while ammonia production will occur on the topside of the platform. Ammonia will be stored either on the platform “or in seabed tanks using water pressure to keep the fuel liquid.”

Fuel will be dispensed either through “bunkering buoys . . . cemented to the seabed or floating in deep water,” or via an additional method: “Bunkering is performed by autonomous units dubbed energy providing vessels (EPVs), powered by offtake from their own cargo and with a range of 50 nautical miles around the mother hubs. The full [ship-to-ship] STS transfer is designed take two hours with both vessels travelling at six knots in a process already proven even in high seas. Drones airlift a pilot cable from the EPV to enable the bunkering hose to be reeled in and mated on the receiving unit.”

The coalition’s modeling indicates that “each hub could potentially produce sufficient ammonia to supply 65 vessels per day.”

ZEEDS is clearly a visionary concept that could play a key role in the maritime sector’s transition to a low-carbon future. But a look at the larger context of the announcement is necessary to see how critical this role could be.

The context starts with the fact that the maritime sector runs predominantly on heavy fuel oil (HFO). HFO can be procured in Rotterdam this week for USD $376 per tonne. This translates to USD $9 per GJ. Diesel fuel purchased on an equivalent basis is priced in the range of $15-$20 per GJ. According to Flexible production of green hydrogen and ammonia from variable solar and wind energy: case study of Chile and Argentina, a paper published last month by IEA Consultant Julien Armijo and IEA Senior Analyst Cédric Philibert, green hydrogen derived from combinations of wind and solar electricity in favorable locales will cost $20-$25 per GJ – before liquefaction and storage. Ammonia derived from this hydrogen will cost $35-$40 per GJ. Substituting any other fuel for HFO, in other words, will cause a major disruption in the economics of ocean freight.

This means that the transition to a low-carbon regime can not be effected by the action of individual companies or through organic evolution of the industry. Any ship that goes into service with a cost position based on an alternative fuel, and price realization based on currently prevailing rates for freight transport, will lose money, likely a great deal of money given that fuel costs represent half or more of total ship operating costs, according to industry sources.

The only way to overcome this challenge is for a governing authority to mandate that all ships in a competitive market must meet a low-carbon fuel standard by a given date (or incur an economic penalty for failure to comply). The obvious governing authority that could do something like this is the International Maritime Organization, the United Nations’ agency that oversees the ocean freight sector. The IMO’s Sulphur 2020 program has established the precedent of a target spawning a mandate, but the progression in this case is likely to be significantly more complex and lengthy.

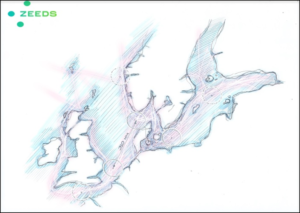

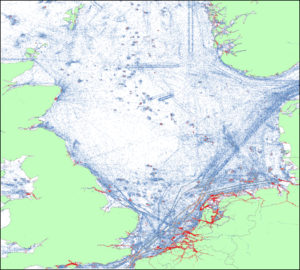

But now consider the stretch of ocean targeted by the ZEEDS initiative – the North Sea and adjacent waters. On the one hand, this area is home to a world-class wind resource. A 2017 study commissioned by industry association WindEurope, Unleashing Europe’s offshore wind potential, focused on “three defined sea basins (the Baltic, North Sea, and Atlantic from France to the north of the UK).” The study found that “offshore wind could in theory generate between 2,600 TWh and 6,000 TWh per year at a competitive cost – €65/MWh (USD $74/MWh) or below, including grid connection and using the technologies that will have developed by 2030. This economically attractive resource potential would represent between 80% and 180% of the EU’s total electricity demand in the baseline and upside scenarios respectively.” And further, “up to 25% of the EU’s electricity demand could, in theory, be met by offshore wind energy at an average of €54/MWh (USD $61/MWh) in the most favourable locations. This assumes seabed-fixed foundations and includes grid connection.”

The Shipping Context. Interreg, undated.

On the other hand, according to EU agency Interreg Europe, these waters are the second busiest maritime zone in the world. Their ports are serviced by the ocean-traversing ships that move goods between continents, and by another complement of ships known as the short shipping fleet. These vessels move exclusively among European ports. The ZEEDS fueling concept appears to be geared for this fleet. Wärtsilä’s Egil Hystad, General Manager of Concept Development, said at the unveiling that fueling operations would be oriented toward ships in “typical North Sea trade.”

In 2001, when the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development published Short Sea Shipping in Europe, 57% of the vessels calling on European Union ports (a population estimated by Interreg Europe to number 7,600) were of less than 6,000 gross tonnage and therefore assumed to be overwhelmingly dedicated to short shipping. (In spite of their numerical advantage, these ships accounted for only 8% of the total gross tonnage servicing the ports.) As the report makes clear, short shipping is a distinct ecosystem that stands apart from intercontinental ocean freight in the specialized nature of its equipment and operations. This means that it could accept a regulatory regime that is not applied to the intercontinental segment without suffering competitive harm. And this means that the IMO, or perhaps another governing authority such as the European Union, could institute a low-carbon fuel mandate just for the short shipping fleet.

This idea appears to be in the minds of the ZEEDS partners, who express a clear desire to involve other stakeholders – “not only industrials and other owners/operators but also politicians, class, academia and financing institutions,” according to the Hellenic Shipping News. One such stakeholder, Thina Saltvedt, Senior Advisor for Sustainable Finance at the Danish bank Nordea, emphasized “the need for closer dialogue with governments to share risk.”

In any case, the coalition partners see extraordinary potential at this early stage. Hellenic Shipping News quoted Andrea Morgante, Wärtsilä’s Vice President of Strategy and Business Development, as saying that the green fueling hubs idea could be “scaled up to serve global trade lanes supplying the world fleet. The [further] vision [would] look beyond just ships. ‘We realised there was a lot of value to be captured in the logistics chain.’”