The social license to operate low and zero-carbon ammonia energy projects

By Kevin Rouwenhorst on September 02, 2022

The third webinar in our series Ammonia Project Features focused on the social license to operate for low and zero-carbon ammonia energy projects. Sam Bartlett (Director for the GH2 Standard & the CO Roundtable, the Green Hydrogen Organisation) and Jonathan Cocker (Partner, Borden Ladner Gervais LLP) discussed societal acceptance and indigenous rights among other topics. The recording is available via our Youtube Channel (you can also download the speaker slides).

The Green Hydrogen Standard

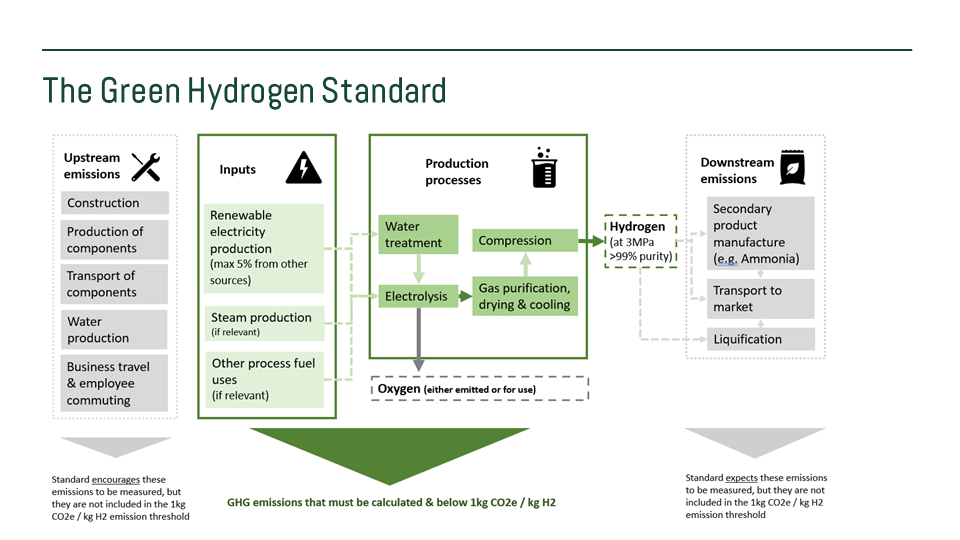

The Green Hydrogen Organisation (GH2) has developed the “Green Hydrogen Standard”, which was launched in Barcelona last May. This allows for trade of renewable hydrogen and its derivatives such as renewable ammonia. Because the meaning of “clean hydrogen” and “low carbon hydrogen” remains ambiguous, producers & consumers need more clarity to make long-term plans, and a standard is required.

Building on existing sustainability methodologies and frameworks

The Green Hydrogen Standard does not stand on itself, but is rooted in existing methodologies and frameworks. For example, the emission threshold for the Green Hydrogen Standard is below 1 kilogram carbon dioxide equivalent emissions per kilogram hydrogen (scope 1 and 2 emissions), which builds on current IPHE methodology. For now, the Green Hydrogen Standard includes the electrolysis-based hydrogen production pathway fed with (almost exclusively) renewable electricity. A few pilot projects are currently tested for future roll-out of the Green Hydrogen Standard. For now, nuclear power and heat, waste to energy, and biomass pathways for hydrogen production are not included.

Clarification regarding the rules of renewable development is required to harmonize low carbon standards under different jurisdictions. For this reason, the Ammonia Energy Association is also developing a certification scheme for low-carbon ammonia as a fuel.

The aim of such a standard is not to differentiate between colors of hydrogen, but rather to be “green” in terms of sustainability and social impact. Thus, the Green Hydrogen standard requires environmental, social and governance consequences of green hydrogen production to be addressed. This is in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations. This is important for a social license to operate, next to the techno-economic viability.

Learning from other industries

In his presentation, Jonathan Cocker reminded us that lessons can be learned from other industries, such as mining or oil & gas extraction. Transparency and accountability are key for local stakeholder trust. For example, a cradle to grave approach was recently introduced in the mining industry, which was spurred by societal pressure. There are also excellent case studies currently in progress to learn from, including Canada’s national Hydrogen Plan and Denmark’s Power-to-X Strategy.

There is significant existing global infrastructure for the hydrogen and ammonia industry, and Ammonia Energy readers are well aware that about 18-20 million tonnes of ammonia is shipped annually around the world. However, the social license of ammonia as a fuel remains uncharted territory.

Empowering local communities

Development of large-scale projects can only be successful with the buy-in of local communities. This is very much defined by ‘what is in it?’ for these communities, and what is the end game after the project development is finalized. As Sam emphasized, If this is not clear at the start of project development, there is a high risk that projects are rejected by local communities. If projects are not properly developed, these can strain local electricity and water resources, while only exporting the produced ammonia.

If done right, such projects can allow for sustained economic development in the region. Indigenous communities often focus economic activities around only a few industries, such as fishing, hunting, and farming. Thus, low and zero-carbon ammonia projects may provide employment opportunities. These projects allow for diversification of activities in indigenous communities, and for skill development, resulting in improved social & economic mobility.

The standard should be set during the very first projects. If not done right, there will be significant backlash for further project development. This point – that botched or rushed first projects endanger the take-off of the industry as a whole – was also raised in our webinars on low carbon, fossil-based ammonia in Europe and North America.

In conclusion, the social license to operate is as important as the technical and economic feasibility. There is no silver bullet for all projects; the social license to operate depends on the location, energy sources, and products of an individual project. Project developers require a strong understanding of local requirements and nuances for sustained, equitable development. This is required at the start of a project – well before governments or local authorities have handed out permits.