Safety Assessments of Ammonia as a Transportation Fuel

By Trevor Brown on June 07, 2018

New data from a number of ammonia energy safety studies will be published later this year. In the meantime, two excellent reports already exist that provide comparative, quantitative risk analyses. Each compares the risks of using ammonia as a fuel in passenger vehicles against the risks of other fuels, including gasoline, LPG, CNG, methanol, and hydrogen. Both conclude that the risks associated with using ammonia as a fuel are “similar, if not lower than for the other fuels.”

The first report, written by Risø National Laboratory in Denmark, examines the risks of using ammonia as a fuel for internal combustion engines and also for fuel cells, and was commissioned as part of the EU-supported project “Ammonia Cracking for Clean Electric Power Technology” in 2005. The second, written by Quest Consultants Inc, was prepared for Iowa State University in 2009 and examined three areas of fuel risk: “bulk movement, storage, and dispensing … The objective of the study was to compute the level of risk posed to the public near an average roadway along which the fuels would be transported in road tankers, and near an automotive fueling station.”

Conclusions: ammonia risk levels are acceptable and similar to current fuels

The Quest report:

In summary, the hazards and risks associated with the truck transport, storage, and dispensing of refrigerated anhydrous ammonia are similar to those of gasoline and LPG …The risks associated with all three fuels would fall into the acceptable category for all referenced risk criteria.

Quest Consultants Inc, Comparative Quantitative Risk Analysis of Motor Gasoline, LPG, and Anhydrous Ammonia as an Automotive Fuel (USA, 2009)

The Risø report:

An overall conclusion is that the hazards in relation to ammonia need to be (and probably can be) controlled by technical and regulatory options …When these safety systems are implemented, the risks of using ammonia is similar, if not lower than for the other fuels.

Risø National Laboratory, Safety assessment of ammonia as a transport fuel (Denmark, 2005)

Ammonia fuel risk is “acceptable” … What does that mean?

The first and most important conclusion we can draw from these studies is that, based on the data, safety should not be an obstacle to the funding, development, or demonstration of ammonia energy projects. As we move from technology development to real-world demonstration installations, site-specific safety analyses will be essential – and data from these will begin to be published later this year – but, immediately, we can examine the existing literature and be confident that the risk levels of ammonia can be adequately managed.

It is important to note, moreover, that this “acceptable” risk profile was achieved in perhaps the highest possible risk scenario: passenger cars in public places. It is likely that initial market adoption of ammonia as an energy vector will take place in remote settings and professionalized sectors where safety and training can be tightly controlled, for example, stationary power generation, or maritime fuel, or economical bulk transport and safe storage and distribution of renewable hydrogen.

Unlike most other proposed alternative fuels, ammonia is already one of the most produced chemicals on the planet, with global production of 180 million tons per year, and international trade and regional distribution of tens of millions of tons per year. This level of activity comes with a 100-year accumulation of safety experience, including know-how for keeping employees and customers safe, a mature international set of laws and regulations, and a sophisticated support sector providing ammonia users and first responders with safety equipment, training, and education. In the words of Norm Olson, former President of the NH3 Fuel Association, almost all the issues surrounding ammonia fuel safety are “engineering problems with engineering solutions.”

The Quest report goes into detail on fuel distribution (truck transport) and service stations, and it describes both the quantitative risks and the engineering solutions available to mitigate those risks.

Truck Transport Safety

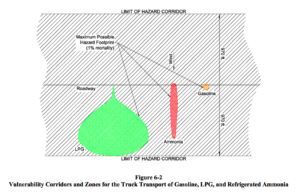

In its review of truck transport safety, which assesses the risks to the public posed by the supply chain distributing fuel from centralized storage to local fueling stations, the Quest report begins with a simple count of the frequency of “releases” per mile in the existing fleet of gasoline, LPG, and ammonia transport trucks.

Today, ammonia has the lowest probability of an accidental release in truck transport.

- Gasoline: 1.75 x 10-7 releases/mile/truck

- LPG: 5.84 x 10-8 releases/mile/truck

- Ammonia: 1.9 x 10-8 releases/mile/truck

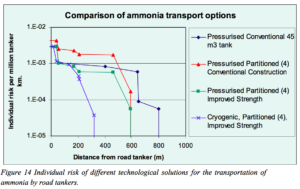

“Nevertheless, risk-reducing options are strongly needed,” and the Risø report illustrates not only how to further decrease the probability of a release but also how to reduce the impact of any such release:

“A solution that causes the risk levels to drop below the risks for LPG requires that ammonia be transported in refrigerated form, in road tankers carrying typically four separated (pressure) tanks of about 11 m3 each, which are as resilient against impact and abrasion as conventional (large) pressure tanks.”

Service Stations

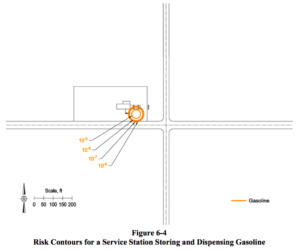

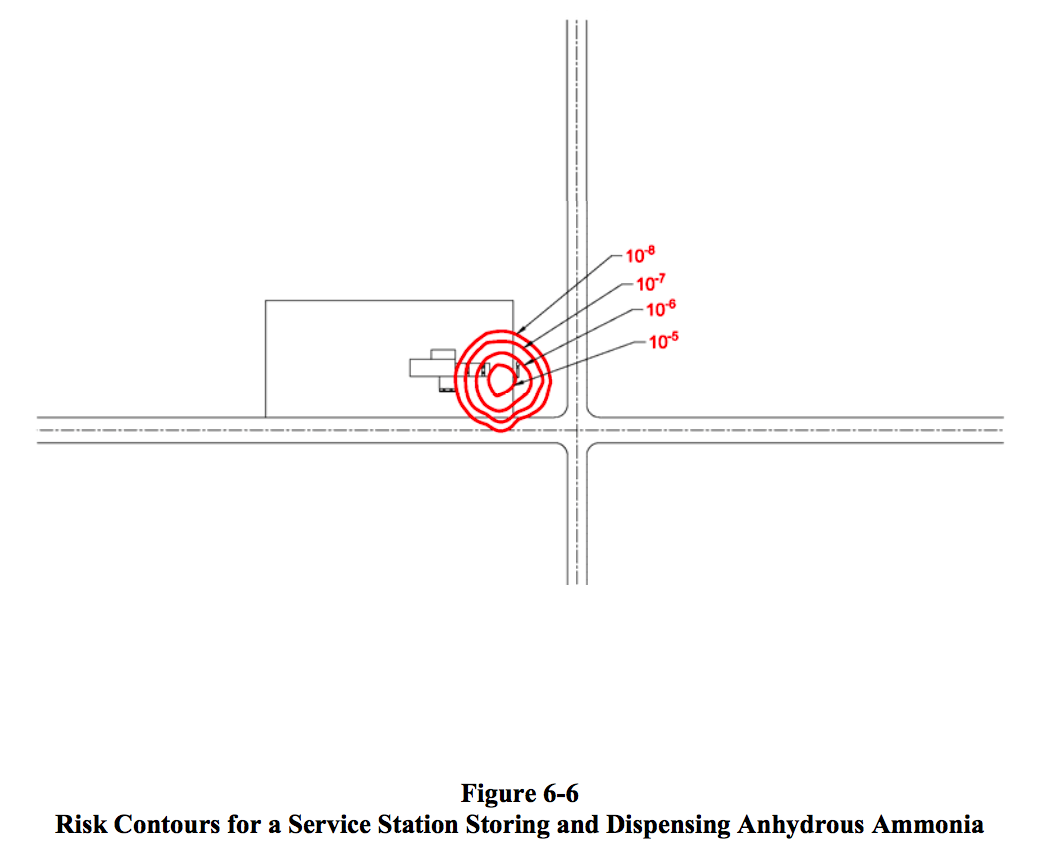

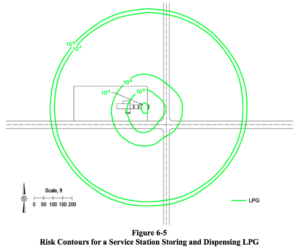

The Quest report provides visualizations of its analysis of the hazards of storing and distributing fuels at a service station located on a road intersection in a populated area.

These “Risk Contours” for Gasoline, LPG, and Ammonia are useful tools for communicating the relative risks of ammonia (colored red) versus gasoline (colored orange) because, at first glance, it is clear that the risk levels of ammonia and gasoline are similar. By contrast, the risk levels for LPG (colored green) are clearly greater.

We already know and accept the risks of distributing gasoline at fuel stations. We also know and accept the risks for LPG in those areas where LPG is utilized as a fuel. Therefore, if we were rational and based our decisions on data, there should be no doubt that we would also accept the risks of distributing ammonia at fuel stations.

And again, I should stress that neither report suggests that we simply accept these risks, because the engineering problems with handling ammonia safely have engineering solutions.

One simple engineering solution is to build a buffer zone around fueling stations:

Small, but long-lasting releases of ammonia due to e.g. leaks and ruptures of hoses, cause serious dangers at distances up to 150 m distance …

This requires additional technical safeguards to reduce the likelihood of these releases (It is especially important to stop the release as soon as possible to interrupt exposure). But also in case these safeguards are in place, safety distances around these ammonia-refueling stations should be no less than 70 m.

Risø National Laboratory, Safety assessment of ammonia as a transport fuel (Denmark, 2005), pp39-40

A more sophisticated solution, which goes further toward eliminating risks, would be to use underground, refrigerated, double-walled storage tanks:

The refrigerated ammonia storage system is designed such that if a small or significant release of ammonia were to occur in the storage, heating, or pumping systems, the released ammonia liquid and vapor would be contained in a vault and vented through a vertical stack extending upward. As the ammonia vapors warm and disperse from the elevated stack, the ammonia/air plume will be positively buoyant and will have no ability to slump back to grade. This storage method essentially eliminates the grade-level risk associated with the storage of refrigerated ammonia.

Quest Consultants Inc, Comparative Quantitative Risk Analysis of Motor Gasoline, LPG, and Anhydrous Ammonia as an Automotive Fuel (USA, 2009), p50 (section 6-10)

Driving a Car

It might be an uncomfortable fact when contemplating fuel safety, but our future fuel choice will probably not be the greatest risk on the road. Speed and human error are far more dangerous.

The fuel used to power a motor vehicle does not contribute significantly to the fatality rate of motor-vehicle accidents …

This conclusion is based on a simple review of the available NSC data and would be expected to be true if anhydrous ammonia were the automotive fuel since anhydrous ammonia would be carried in a

pressure vessel similar to LPG.

Quest Consultants Inc, Comparative Quantitative Risk Analysis of Motor Gasoline, LPG, and Anhydrous Ammonia as an Automotive Fuel (USA, 2009), pp9-10 (sections 1-3, 1-4)

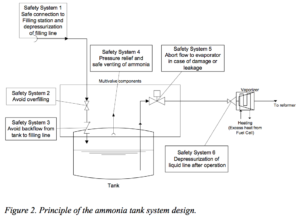

Nonetheless, the Risø report describes the engineering solutions to the engineering problems and provides specifications for an onboard fueling system that includes additional safety systems.

For example, the fuel tank itself (“consisting of carbon fibres with a inner lining of polyethylene”) is designed so that the “advantage over steel tanks is that it excludes (which has been proven for LPG) explosive failure of the tank in a fire.”

Ammonia Fuel Risk Levels: “Similar, if not Lower than” Gasoline, LPG, Methanol, Natural Gas, and Hydrogen

The main point here, beyond providing links to the two reports for those who wish to read further, is to demonstrate that ammonia safety should not be a barrier to the development and demonstration of ammonia fuel technologies.

This post is based on a presentation I gave at Argonne National Laboratory, on September 22, 2015, at the twelfth annual NH3 Fuel Conference: Ammonia Fuel Risk Levels: “Similar, if not Lower than” Gasoline, LPG, Methanol, Natural Gas, and Hydrogen. On the same morning that I delivered the presentation, the news broke that Volkswagen had admitted wrongdoing in the defeat device emissions scandal, which became known as Dieselgate. I quoted the statement of Michael Horn, President and CEO of the Volkswagen Group of America: “Let’s be clear about this, our company was dishonest – with the EPA, and the California Air Resources Board, and with all of you. And, in my German words, we have totally screwed up.”

The point I made that day, which stands even more strongly today following the growing bans of gasoline and diesel cars – outlawed in Norway from 2025, in Scotland and Sweden from 2032, across the whole UK and France from 2040 – is that in our consideration of future fuel safety we should be comparing the manageable risks of ammonia, which are immediate and internalized in the fuel risk profile, against the unmanageable risks of refined fossil fuel combustion, which are long-term and externalities, causing health impacts far from the point of use.

Ammonia is a hazardous chemical and it must be treated with respect, and also it can be an excellent fuel. As the Risø report concludes, “the acceptance of ammonia will not be based on the results of numerical risk analysis, but will also be influenced by the public’s perception of the threats of ammonia.”