Chicken or Egg? GH2 proposes solutions to the off-take trilemma

By Oscar Pearce on June 20, 2024

Click to learn more. The Green Hydrogen Organisation have released a report on off-take considerations (GH2, May 2024).

The Green Hydrogen Organisation (GH2) has released a report sketching out considerations for hydrogen off-take agreements. The report follows research from BloombergNEF that found that only 10% of clean hydrogen capacity planned by 2030 has currently identified a buyer. The GH2 report discusses the importance of balancing risks between prospective buyers and sellers through, among other things, carefully calibrated pricing mechanisms and volume regulation.

A trilemma

GH2 is mindful of three interconnected problems in scoping out off-take challenges for green hydrogen and derivatives.

First, there is not yet a ‘liquid’ market for green hydrogen and derivatives. Rather, producers are highly incentivised to craft bespoke off-take arrangements, since they cannot send excess volume to a mature, easily-accessible commodity exchange.

Second, without a liquid market, there are not readily identifiable market prices for these products (though ammonia is, of course, an exception). Specifically, despite some emerging efforts, there is not a settled underlying price index that parties can use as a basis (eg. the indexing of conventionally-produced ammonia to the price of gas feedstock).

Finally, GH2 argues that there is inherently more uncertainty in the production of green hydrogen and derivatives. Where there is dependence on wind or solar energy as key inputs, there is exposure to the basic risk of intermittency.

The consequence of these three challenges is that producers and off-takers must negotiate how to distribute a significant amount of risk, without battle-tested models and price indices to guide their decision-making.

Setting prices without a crystal ball

GH2’s report does not offer a silver bullet solution to the off-take trilemma, but it does indicate some promising options.

In terms of pricing arrangements, there are (broadly-speaking) two conventional categories: fixed and variable. Fixed prices are ordinarily calculated based on production costs plus an agreed margin of return, while variable costs are pegged to some form of market price index.

This dichotomy masks a wide spectrum of approaches in each category. For example, fixed price schemes could operate based on anticipated production costs or instead adopt a ‘cost-plus’ model, where costs are calculated with certain limits. The first approach assigns the risk of production cost volatility to the producer, while the second assigns it to the off-taker. Alternatively to these two options, producers and off-takers may settle on a mixed arrangement with fixed and variable components combining to determine the price.

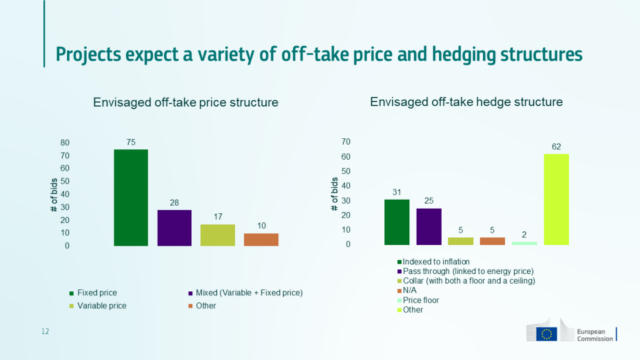

Click to expand. European Hydrogen Bank bidders gravitated towards a fixed offtake price, while using a range of hedge structures. (European Hydrogen Bank, Apr 2024).

While GH2 does not discuss the current prevalence of each of these approaches, the results of the European Hydrogen Bank auction in April were revealing. There, a majority of bidders opted for fixed off-take pricing. While noting again the breadth (and thus ambiguity) of these categories, it is telling that the market appears reluctant to adopt variable models at this early stage.

There are strengths and weaknesses to each of these approaches, and GH2 does not advocate for one in particular. It does, however, make some general recommendations.

Firstly, GH2 notes that most schemes that have successfully secured offtake agreements are “integrated”. By incorporating the offtaker as an investor, joint developer, or some other equity partner on the production side, it is easier to achieve trust, cooperation and balanced risk distribution.

Secondly, GH2 advocates for carefully designed price review mechanics. While acknowledging the importance of price certainty, GH2 argues it is worthwhile to allow for variation of the pricing model following certain trigger events (e.g., the establishment of a consensus market price index for hydrogen). While such mechanisms may increase the risk of dispute between the contracting parties, GH2 argues that that risk should be tolerated.

Regulating supply volume

In addition to price, the other key component of off-take agreements is volume regulation. Here, the tension between producers and off-takers is even more straightforward. Producers desire strict ‘take-or-pay’ obligations, where off-takers are obligated to purchase the entire contracted production quantity, regardless of future changes in their demand. In contrast, off-takers will want to avoid any obligation to purchase surplus to demand, while holding producers to minimum supply obligations (‘send-or-pay’).

GH2 argues that this challenge must be resolved by finding a middle ground. Specifically, ‘take-or-pay’ obligations can be softened to incentivise (but not bind) off-takers to accepting the full quantity. Likewise, minimum production thresholds can be lowered, such that producers are not fatally exposed to adverse input prices. Moreover, GH2 argues that joint ventures and equity sharing are again a means of effectively balancing the so-called ‘volume risk’.

Conclusion: balance interests, build trust

These challenges are not intractable, but nor are they straightforward to address. The GH2 report, which can be read in full here, also highlighted the importance of provisions relating to certification, force majeure and regulatory change. In each of these cases, GH2 argues that it is possible to achieve a balance between the interests of producers and off-takers, and thereby build the trust that is vital to this emerging market.