The Korean New Deal and ammonia energy

By Julian Atchison on April 15, 2021

South Korea has featured in many Ammonia Energy news updates, but often in a scatter gun fashion that lacked the momentum of ammonia energy announcements coming from the other side of the Korea Strait. Now, South Korea is ready to step out from Japan’s shadow as a clean energy innovator and deployer in its own right.

Late last year President Moon Jae-in declared his country would be carbon neutral by 2050, setting down a massive challenge. South Korea still relies on thermal coal for 40% of its electricity and has a relatively small amount of installed renewable energy generation. There’s also the issue of decarbonising South Korea’s significant heavy industry, transport and shipping sectors. Details of the “Korean New Deal” (of which the Korean “Green New Deal” is a part) were released in mid 2020, but, besides ramping up the use of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, calls for a “just transition” for coal workers and support for the build-out of renewable power, there were few tangibles.

This has changed in 2021. With the implementation of a world-first, national Hydrogen Law by the Moon Jae-in government, we’re seeing the beginnings of a well-articulated strategy to achieve society-wide decarbonisation in South Korea with a starring role for clean hydrogen and clean ammonia. Several recent announcements demonstrate this new national focus.

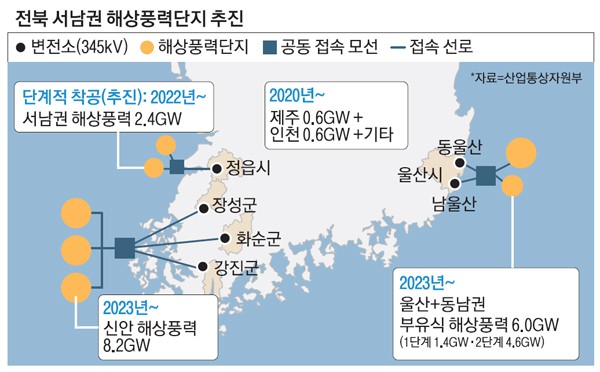

Huge offshore wind ambitions

In February the Moon Jae-in government announced state backing for the world’s biggest planned offshore wind farm: the 8.2GW Sinan project in the Yellow Sea. A consortium of thirty-odd Korean organisations – including KEPCO, the country’s biggest power utility – will collaborate on the KRW 48.5 trillion project (US $43.5 billion). Ostensibly, the enormous capacity of Sinan is a bid to substitute thermal coal and nuclear power generation in the country for renewable energy, but the location of the wind farm could lend its generating capabilities to other applications.

The Sinan Islands are about seventy kilometers from the nearest substation on South Korea’s national high-voltage transmission network, and will only be connected to the very fringes of the country’s power grid. This raises the issue of new cross-country transmission lines being built and upgrades to the existing grid: both have been notoriously difficult to achieve (this report from Solutions for Our Climate outlines these and other obstacles facing new build renewable energy projects in South Korea).

Sinan is also on the doorstep of Yellow Sea shipping routes and the incredibly busy north-south lanes that run along coastal China through Shanghai. Access over water to South Korea’s coastal-based industries — particularly steel making, ship building and heavy manufacturing — is also straightforward: either north to Seoul or around the peninsula to Busan (which is planned to host offshore wind projects of its own). Sinan therefore has the potential to act as a grid-generating facility and a power source for hydrogen and ammonia production with easy transport to key markets (both internal and external).

We only need to look to Europe for precedent. The concept of dramatic offshore wind overbuild, with the knowledge that any “spare” generation not sent to electrical grids can be used for hydrogen production, is fast gaining traction in the North Sea with projects like Denmark’s Energy Islands and the Aquaventus Initiative. The use of GW scale offshore wind for dedicated ammonia production is also on display in Denmark, where CIP, Maersk and DFDS Shipping are planning Europe’s biggest power-to-ammonia facility.

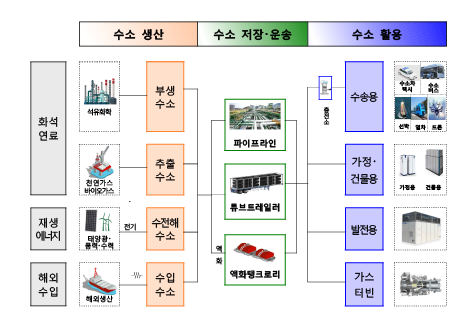

Import of green hydrogen as ammonia

Ramped-up domestic production of green hydrogen and ammonia makes perfect sense for South Korea. Last month a deal was signed between Australia-based Origin Energy and steelmaker POSCO for the supply of green hydrogen in the form of green ammonia, produced at Origin’s to-be-developed, hydro-powered ammonia production facility in Bell Bay, Tasmania. Although POSCO is aiming for the import of zero-carbon feedstock to be only temporary, the sheer scale of their goal to produce 5 million tonnes of clean hydrogen in South Korea by 2050 is readily apparent. POSCO’s domestic hydrogen production currently stands at only 7,000 tonnes per year (completely fossil-based), so this transformation will represent a more than 700x increase in local production capacity for one steelmaker alone. Many more Sinan wind farms and ammonia import agreements will be required for decades to come if other South Korean organisations and industries set their sights similarly high. Even the South Korean government’s official forecast for a need for 7 million tonnes of imported clean hydrogen a year by 2040 (Korean press release) may end up being highly conservative.

Cracking R&D

At the same time as POSCO announced its agreement with Origin, it also announced a new R&D partnership with KIST (Korea Institute of Science & Technology), and RIST (Research Institute of Industrial Science & Technology) to develop ammonia cracking. As discussed at our Ammonia Energy Conference in November 2020, the advent of turnkey, modular and affordable cracking solutions is still on the horizon, but organisations are keen to know if a business case can be made once technical and energy efficiency improvements have been achieved. Exactly what the focus of this R&D relationship will be is yet to be decided on, but we have only to look to another South Korean organisation for inspiration. Hyundai’s work with CSIRO and Fortescue on developing an ammonia to high-purity hydrogen system for PEM fuel cell vehicles is coming along well and will dovetail neatly with the Moon Jae-in government’s new focus on hydrogen-powered vehicles. South Korea also has a hugely successful research pedigree to draw from in these pursuits: both the Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology (KAIST) and the Korea Institute of Energy Research (KIER) have been presenting work on electrochemical ammonia synthesis, cracking and ammonia combustion at AEA conferences for some time now. Stay tuned for further South Korean R&D developments throughout 2021.

Blue hydrogen and ammonia partnerships

And, while the transition accelerates, South Korean organisations have moved this year to secure access to blue hydrogen and ammonia in the Middle East. GS Energy will help ADNOC develop blue hydrogen and ammonia supply value chains in Abu Dhabi, while Hyundai Heavy Industries and Saudi Aramco are working together on R&D and feasibility studies for ammonia as a low-carbon power generation and shipping fuel. In the wake of Aramco’s first shipment of blue ammonia to Japan last October these moves come as no surprise, though it is a pressing reminder that development of rigorous global certification standards are required to ensure the low-carbon bona fides of any blue product. It’s worth noting too that the focus of the “Korean New Deal” and all subsequent announcements from the Moon Jae-in government have been heavily focused on green, renewable technologies, indicating demand for blue hydrogen and ammonia may be short-lived in South Korea.