Work in progress: MEPC 82 lays the groundwork for final decisions in 2025

By Oscar Pearce on November 20, 2024

Click to learn more. The IMO’s Maritime Environmental Protection Committee has held its 82nd meeting, laying the groundwork for key decisions set to be made at MEPC 83 in April 2025.

The IMO’s Maritime Environmental Protection Committee (MEPC) held its 82nd meeting in October 2024. Building on MEPC 80 and 81, the Committee was tasked with the ongoing development of the IMO’s “mid-term measures” to cut GHG emissions from the global shipping industry. Central to these negotiations is the debate over what sort of economic measure to implement: a levy (or “feebate”) mechanism, a flexible credit trading system, or both. This debate will be resolved at MEPC 83 in April 2025. In addition to raising decarbonisation funds, MEPC 82 saw progress in discussions on the distribution of those funds, and the pursuit of a just transition that includes all the IMO’s member states.

Contours of the GHG pricing debate

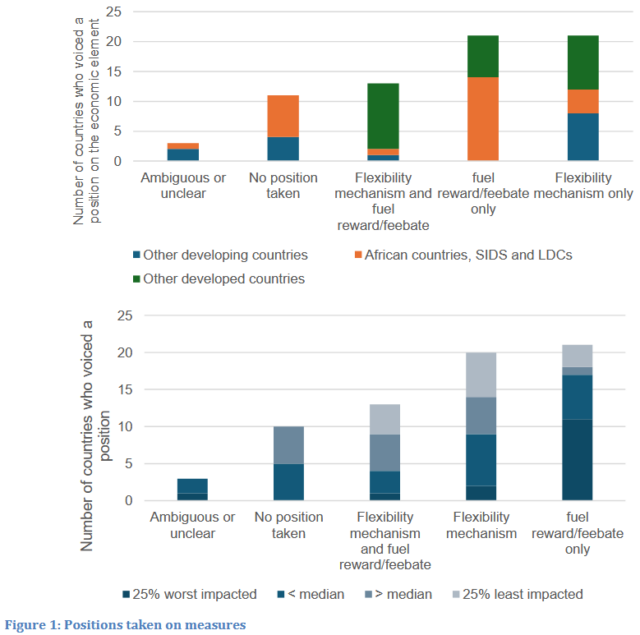

While it is certain that the IMO’s mid-term decarbonisation measures will feature an “economic mechanism”, the architecture of that mechanism remains uncertain. Interestingly, the number and composition of states in favour of the various options has remained largely consistent since MEPC 81.

Click to expand. Countries’ preferences on the design of the IMO’s mid-term economic mechanism (UCL Bartlett Energy Institute, Oct 2024).

Ahead of MEPC 81 in March 2024, UMAS reported mixed stances on this debate. Of the countries that expressed a clear stance, 14 mostly middle-income countries supported a credit trading mechanism without a further GHG levy. 18 primarily Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) preferred a levy without credit trading. Finally, 16 predominantly developed countries supported a combination of both.

UMAS now reports that there was a similar distribution at MEPC 82. Overall support for exclusively implementing credit-trading (14 to 21) and a levy (18 to 21) has increased, while support for a combination has remained stable (14 to 13). The socioeconomic composition of these tallies has remained largely stable. In particular, SIDS and LDCs have remained firmly in support of a universal levy. Relatedly, the levy also enjoys the strongest support from those countries that are projected to be most impacted by the maritime energy transition. At MEPC 82, there were 14 member states that either did not take a position, or their stance was unclear

Fund distribution to ensure a just transition

A key priority for negotiators has been ensuring that revenue generated through the chosen mechanism is utilised appropriately. This has been a particular point of emphasis for those countries most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and the economic implications of stricter shipping regulations. MEPC 82 advanced discussions on how revenue could be allocated to minimise adverse effects on low-income states, and facilitate equitable access to green technologies.

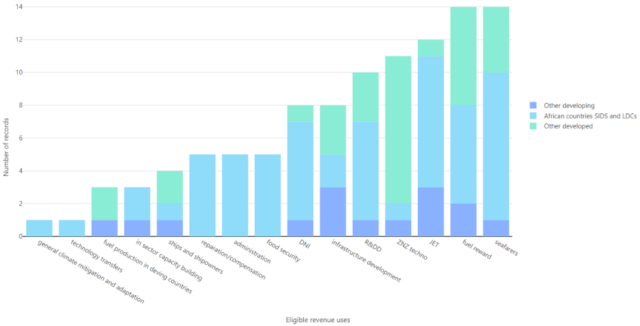

Click to expand. Participants in MEPC 82 highlighted various possible uses of revenue generated by the IMO’s mid-term economic mechanism (UCL Bartlett Energy Institute, Oct 2024).

A range of revenue uses were raised by delegates. The most supported suggestions included:

- for revenues to be disbursed as a “fuel reward” for over-performance

- support and training for seafarers

- investment in research and development

- and ensuring a just and equitable transition (although the precise revenue distribution implications of this are not yet clear)

There are important trade-offs between these distribution proposals. Simply rewarding over-performance in the transition is likely to bolster developed economies with existing strengths in green technology. Further, landlocked nations observed that they would be vulnerable to increased shipping costs (when passed along in increased import prices) but would derive no direct benefit from in-sector investment in the maritime sector.

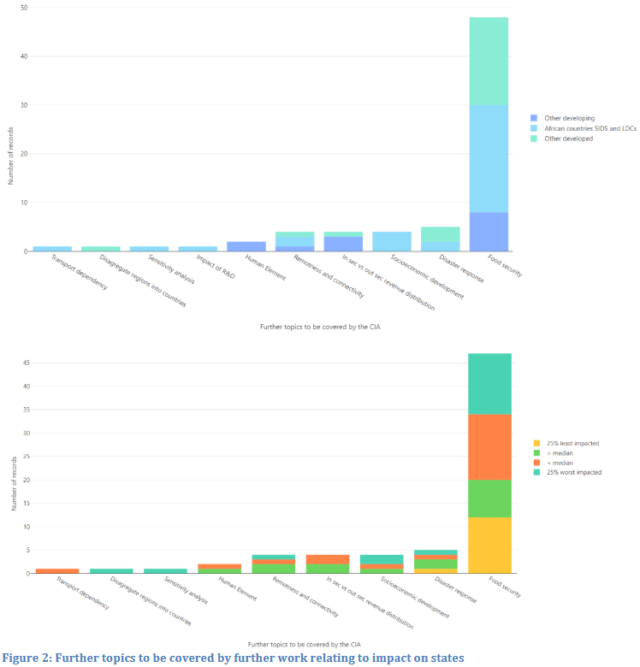

Click to expand. Participants in MEPC 82 showed particular concern for the food security implications of the maritime energy transition (UCL Bartlett Energy Institute, Oct 2024).

Discussions regarding revenue distribution at MEPC 82 were shaped by the impact assessment conducted by UNCTAD (which can be viewed on IMODOCS). An issue with particular salience was that of food security, which received largely indirect attention in the UNCTAD assessment. A concern expressed by many states was that GHG pricing would increase the price of food imports, a phenomenon that may not be mitigated by investment in green technology.

Path to MEPC 83

At MEPC 83 in April 2025, and the intersessional meetings in the meantime, states will have to make relatively rapid progress in solidifying the IMO’s mid-term measures. In addition to the issues outlined above, all manner of practical matters will need to be resolved, including settling on a start year. This is not an unreasonable timeline, but it means the exact balance the IMO will strike between justice, efficiency, and sustainability will remain uncertain for another four months.

You can read UMAS’ full breakdown of proceedings here.