Japan, Saudi Arabia Explore Trade in Hydrogen, Ammonia

By Stephen H. Crolius on February 15, 2018

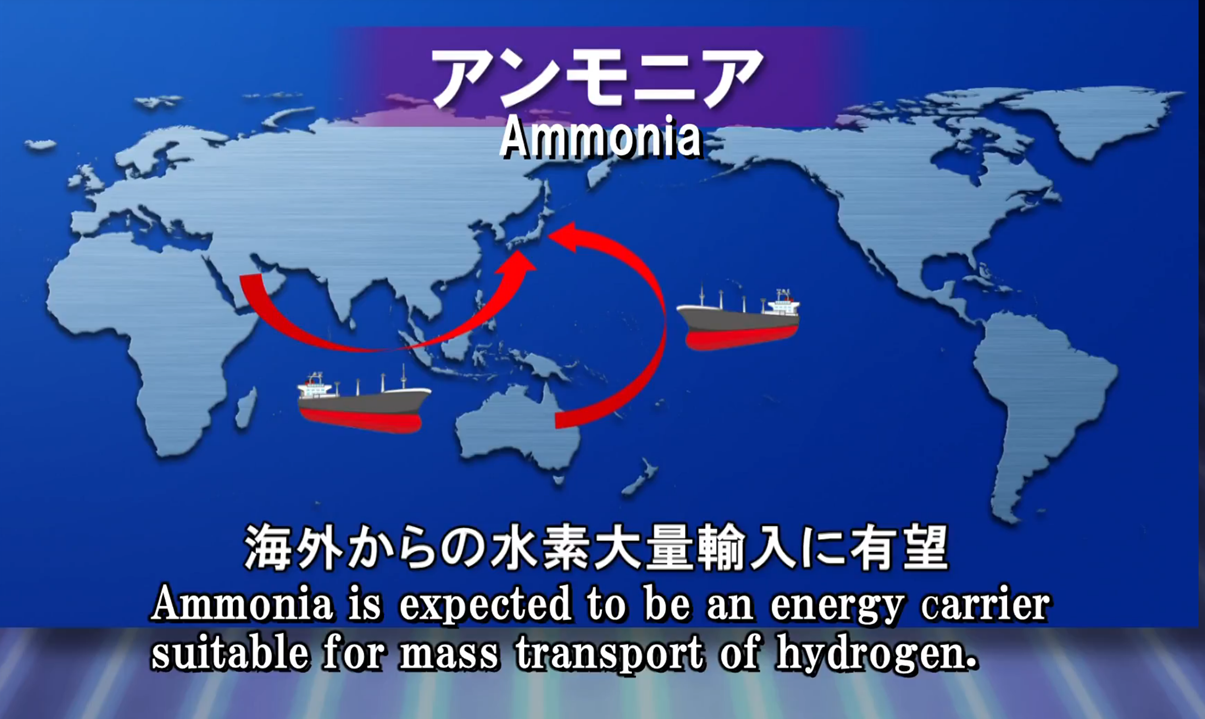

Japan and Saudi Arabia are together exploring the possibility of extracting hydrogen from Saudi crude oil so that it can be transported to Japan in the form of ammonia. According to a synopsis of the planned effort, “one option for Japan’s material contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions [would be] a supply chain for carbon-free hydrogen and ammonia produced through CCS from Saudi Arabian fossil fuels.”

The synopsis emerged from a September 2017 workshop sponsored by Saudi Aramco and the Institute of Energy Economics, Japan (IEEJ). Saudi Aramco is a state-owned oil company that is responsible for approximately 10 percent of the world’s petroleum production. The IEEJ describes itself as a “think tank” whose mission is to contribute to Japanese energy policy.

The discussions about hydrogen supply are the tip of a massive iceberg of high-level diplomacy between Japan and Saudi Arabia. In September 2016 Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman established the Joint Group for Saudi-Japan Vision 2030. The contemporaneous briefing document voices an intention to build on the long-term relationship between the two countries: “Saudi Arabia has been the largest and stable oil supplier for Japan, and Japan has been one of the largest customers for Saudi Arabia.” In the document Abe affirmed that “Japan is ready to help with the implementation of the Vision 2030 plan by reducing Saudi dependence on oil.”

In the 16 months since, according to a progress report, officials from the two countries have organized an effort that consists of three pillars, nine themes, and 46 government projects. The latter are arranged into six sub-groups that are being overseen by 44 ministries and government agencies. Sub-group three, Energy and Industry, is being led by the Ministry of Energy, Industry, and Mineral Resources (MEIMR) on the Saudi side and the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) on Japanese side. Saudi Aramco is one of six entities supporting the MEIMR on the Saudi side. METI announced its new hydrogen strategy two months ago, in which it established a roadmap for the first commercial imports of “CO2-free ammonia” as a hydrogen energy carrier “by the mid-2020s.”

Saudi Arabia is one of the world’s top three oil producing nations, and the ninth largest producer of ammonia. The Saudi government is planning an initial public offering of Aramco shares later this year. According to a report in Forbes magazine, “the Aramco IPO is part of a larger national transformation plan that young Deputy Crown Prince (the second in line for the crown) has engineered. This plan, called Vision2030, encourages the Saudi economy to diversify and reduce its economic dependence on oil and gas. The Saudi government intends to use the proceeds from its 5% sale of Aramco to fund investments in its massive Public Investment Fund (PIF).”

One outcome of the September Aramco/IEEJ workshop, according to the synopsis, was a “common understanding on the element technologies in the supply chain including CCS and EOR, energy carriers, and the use of hydrogen and ammonia.” While CCS (carbon capture and sequestration) is generally regarded as an approach that, at least in theory, could be used in large-scale schemes to produce “carbon-free” hydrogen from fossil fuels, the case for EOR (enhanced oil recovery) is less clear.

EOR is a form of CCS that has been in use since the 1950s. It involves injection of CO2 into underground fossil energy deposits to achieve more thorough extraction. EOR’s obvious flaw as a carbon sequestration technique is that it directly results in more carbon being forced from the depths of the earth. The journal Power examined the ratio between carbon sequestered and carbon produced via EOR and concluded that each “ton of CO2 used in EOR is bringing up roughly 0.76 to 0.91 tons of equivalent CO2 that will ultimately wind up in the atmosphere.”

Policy makers in Saudi Arabia are aware of international efforts to address climate change and the challenge such efforts pose to the Saudi economy. The country’s approach to the topic was illustrated by a gathering of “more than 30 energy experts” in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in December 2017 “to discuss how oil producers can thrive through a low carbon energy transition.” The Saudi Gazette reported that “the objective of the workshop was to develop effective strategies for mitigating the economic impacts on fossil fuel suppliers of decarbonization policies.” The Saudi government featured EOR as one its main “carbon management” strategies at a World Bank workshop in 2011 and in many communiques since.

Questions about the climate-friendliness of hydrogen produced in association with EOR aside, a near-term objective of the Japanese-Saudi study group is “assessing the feasibility of JCM” and “the acquisition of bilateral credits for FY2017.” The Joint Crediting Mechanism was proposed in 2011 by the Government of Japan as a way to “facilitate the diffusion of low-carbon technologies” from developed to developing countries. The ultimate goal is garnering credits for greenhouse gas reductions that can be shared by Japan and partner countries. Sixteen other countries, primarily in Asia, have since signed the JCM partnership document.

Although ammonia has a prominent position within the Vision 2030 process, it is not the only hydrogen carrier under consideration. Chiyoda Corporation, a leading proponent of the liquid organic hydride methyl cyclohexane, is one of 67 companies that visited Riyadh last month as part of a trade mission. And Iwatani Corporation, Japan’s largest hydrogen distributor and a leading proponent of liquid hydrogen technology, announced last week that it was entering into negotiations with Aramco toward an arrangement that could involve extracting hydrogen from crude oil, liquefying it, transporting it to Japan, and managing its in-country distribution. Iwatani has an existing agreement with Saudi Aramco that involves the supply of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).

In the meantime, the IEEJ “will conduct a feasibility study on the supply chain for carbon-free hydrogen and ammonia and, based on the discussions at [a] second workshop to be held in Saudi Arabia in December [2017], will finalize the master plan.”