Setting the scene for ammonia maritime fuel: regulatory needs and timelines to decarbonize shipping

By Julian AtchisonKevin RouwenhorstAndrea Guati RojoTrevor Brown on March 21, 2025

*the authors would also like to thank Niel de Vries, Head of Energy at C-Job Naval Architects, for his input to this article

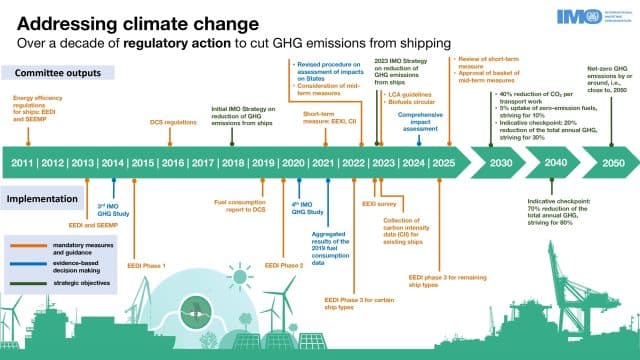

Click to enlarge. Overall timeline for regulatory action to address GHG emissions at the IMO. Source: International Maritime Organisation.

2025 is a critical year for the adoption of ammonia fuel in shipping. Here, we will explore the various initiatives in-progress at the International Maritime Organization (IMO), and what headlines to look out for over the course of this year. A second – and very important – question is whether all this work actually fills the regulatory gaps, and what else may be required. This year also marks an important milestone with the commercial arrival of the first two-stroke engines. All this sets the scene for incredible progress to be made in the coming years.

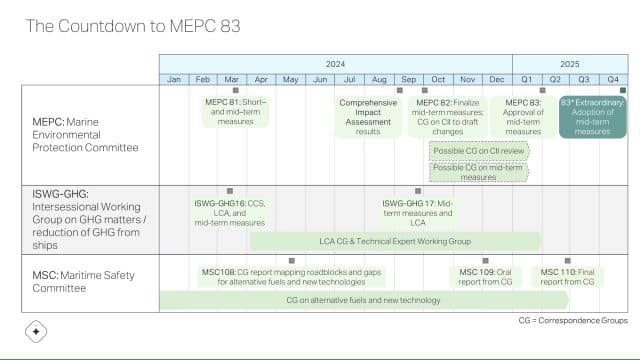

Upcoming IMO meetings in 2025

All eyes are on the upcoming meetings of the IMO’s Maritime Environmental Protection Committee meeting in April this year (MEPC 83). After progress made at the last meeting (MEPC 82) in October 2024, the global shipping industry now waits to see what “mid-term measures” for emissions reduction will be formally proposed – and particularly what a GHG pricing mechanism for global shipping will look like.

Click to enlarge. The countdown to MEPC 83 – key decision points and events. Source: Maersk McKinney Møller Centre for Zero Carbon Shipping.

Among the IMO member states, support for a GHG levy continues to increase, with funds to be disbursed annually to support the accelerated uptake of alternative fuels, and to support maritime decarbonization in smaller member states. There is also support for a goal-based global fuel standard, mirroring the EU’s FuelEU Maritime rules.

MEPC 83 will also feature discussions on boundaries for emission reductions. Since 2023 the AEA has added its voice to the calls for the global shipping industry to take a “well-to-wake” approach for emission reductions, instead of the current “tank-to-wake” approach. As well as MEPC 83 in April, an extraordinary session of the committee will be held in October 2025, with the intention of formalising and adopting proposals discussed this April.

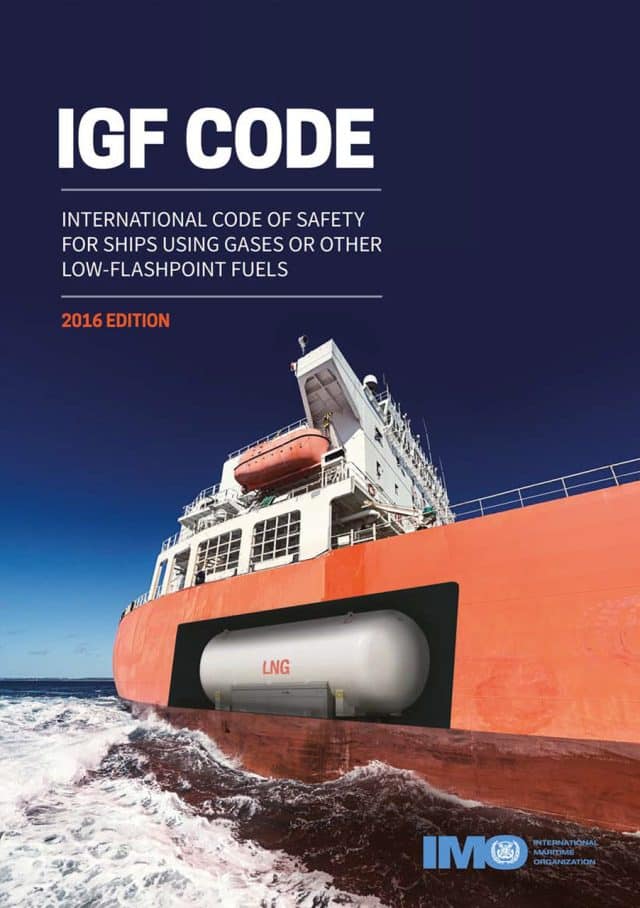

Click to learn more. The Maritime Safety Committee is exploring amendments that need to be made to the IGF Code to accommodate ammonia fuel.

In June, the Maritime Safety Committee meets for MSC 110. It was at MSC 109 last December that the IMO adopted its first-ever guidelines for vessels fueled by ammonia, including a range of vessel design and safety system requirements. At MSC 110, further discussions will be held on what changes need to be made to the IGF and IGC Codes to accommodate new fuels, and particularly the use of ammonia cargo as fuel (which is currently prohibited). Draft interim guidelines for using ammonia as cargo and fuel under the IGC Code are expected to be finalized at another meeting this year – the Sub-Committee on Carriage of Cargoes and Containers (CCC 11) – in September, formally removing the prohibition and opening the door for ammonia-fueled, ammonia gas carriers to operate.

And we also have the Sub-Committee on Human Element, Training and Watchkeeping (HTW), which just met this February. HTW announced that a working group has been tasked with producing draft guidelines for the training of seafarers onboard ammonia-fueled ships. The guidelines will be presented at the next meeting of the HTW (currently unscheduled). In parallel with code development at the IMO level, a number of new seafarer training initiatives have been launched in 2025, and the issue has swung sharply into focus for the shipping industry.

Regulatory gaps – are they being filled in 2025?

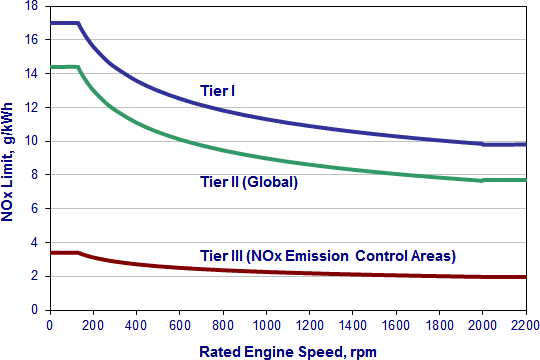

With so many moving parts at the IMO, it is worth pausing briefly and double-checking what regulatory gaps are actually being filled – or not – with these decisions. Current IMO regulations on vessel emissions cover three areas: NOX, SOX, and greenhouse gases. In the case of SOX emissions, ammonia fuel represents an immediate benefit: depending on the pilot fuel used (and in what amount), sulphur-based emissions are reduced to near-zero, and in some cases eliminated completely.

Click to enlarge. IMO Tier regulations for NOX emissions, plotted against rated engine speed. Source: AMarine Blog.

In the development of ammonia-fueled engines, technology developers have long emphasized that their goal is to meet (at a minimum) Tier II NOX requirements with engine operations, and then Tier III requirements with the application of DeNOX treatment to the engine exhaust. Testing results from a number of engine developers (including Wärtsilä, MAN ES, WinGD, and IHI) indicates that ammonia-fueled engine platforms will produce NOX emissions comparable to engines fueled by heavy maritime oil (in some cases, even lower). Regardless of these test results, the use of DeNOX (SCR) systems is still envisioned to mitigate both NOX and ammonia slip emissions.

The other key nitrogen-based pollutant molecule – with a GHG warming potential well above that of CO2 – is nitrous oxide, or N2O. While N2O is not technically regulated by the IMO (currently), its GHG potential means it will definitely be included in future emissions reporting, and thus controlled by future emissions regulations. This will certainly be included in any “well-to-wake” lifecycle emissions approach (see below).

The same engine developers focused on NOX emissions also report successful tests demonstrating that N2O emissions can be likewise minimised or completely eliminated (for example, WinGD reported <3ppm emissions for full-load testing earlier this year). There is a general consensus that the use of ammonia fuel cannot replace a carbon emissions problem with a nitrogen emissions problem. This consensus is – thankfully – shared by developers of ammonia-fired gas turbines, and those pursuing ammonia-coal co-firing. So, although there is a regulatory gap here currently, the minimization of N2O emissions is still well within focus for technology developers. N2O emissions reduction is envisioned in both combustion optimization and after treatment with a dedicated catalyst (this is already proven or “off-the-shelf” technology in onshore applications, and some existing DeNOX catalysts can also eliminate N2O emissions).

Greenhouse gas regulations for shipping are totally focused on CO2, with a number of measures in place. For ships themselves, there are three areas:

- EEDI (Energy Efficiency Design Index) for newbuild vessels, promoting the use of more energy efficient equipment and propulsion aboard newbuilds

- EEXI (Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index) for existing vessels, an efficiency assessment applied to existing ships, introduced at the same time as the EEDI

- And CII (Carbon Intensity Indicator), a continuously-monitored assessment of a ship’s energy efficiency, given in grams of CO2 emitted per cargo-carrying capacity and nautical mile.

By themselves, these regulatory measures are not enough to promote the uptake of new maritime fuels. For EEDI, electrification, design optimization, the use of wind-propulsion and other energy saving measures are all strategies currently used by shipowners to meet requirements. EEDI and EEXI were introduced in 2013, meaning most – if not all – existing vessels have already completed their EEXI assessments, and have no further requirements. CII has gone some way to encouraging decarbonization, but the “per cargo-carrying capacity” element of the calculation means the measure is – unfortunately – open to abuse. The emissions footprint of a vessel is almost entirely based on its operational lifetime (>95%), so decarbonization measures for vessel fuel are needed.

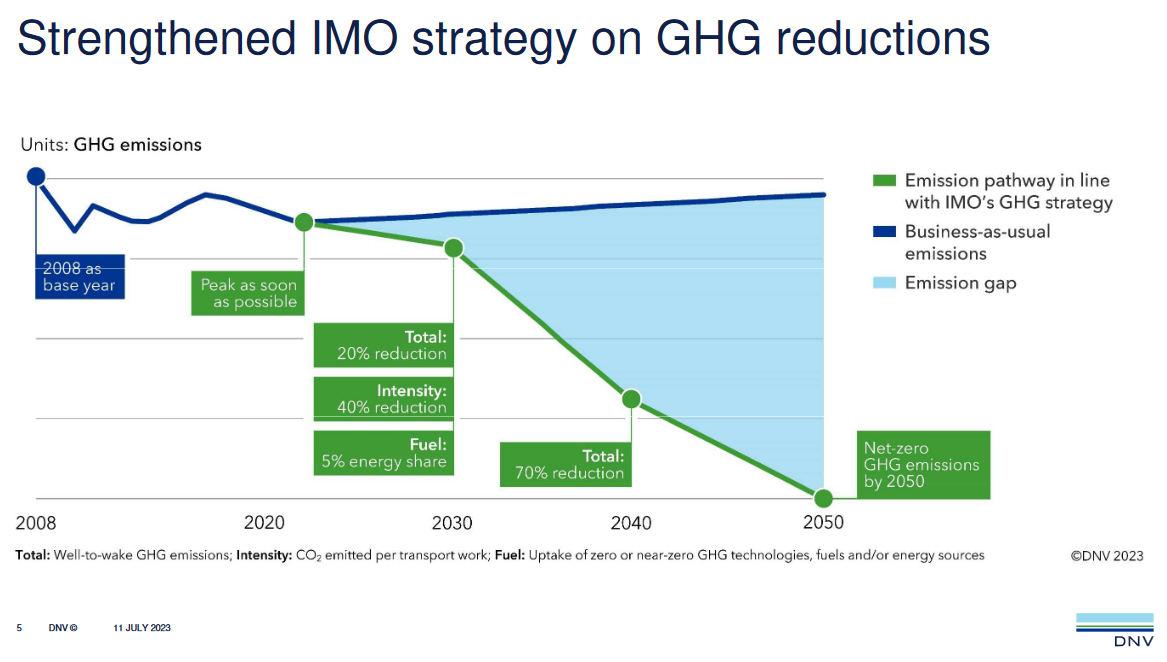

Click to enlarge. The IMO’s goals for greenhouse gas emission reductions. From MEPC 80: Increased emission reduction ambitions in revised IMO GHG strategy (DNV, July 2023).

The industry-wide GHG emission reduction goals set by the IMO in 2023 go some way towards filling this gap. By setting absolute targets (20% below 2008 baseline levels in 2030, 70% in 2040 and net-zero in 2050), alternative fuels like ammonia are now necessary for ships to meet their regulatory requirements. Indeed, the IMO has officially set itself an alternative fuel uptake target: “uptake of zero or near-zero GHG emission technologies, fuels and/or energy sources to represent at least 5%, striving for 10%, of the energy used by international shipping by 2030.”

But targets must be followed by measures that encourage stepwise progression, including interim check-ins on progress, and targeted financial support. Ahead of MEPC 83, the two leading contenders for these measures propose to address the regulatory gap in different ways.

Levy on all emissions, or goal-based fuel standard?

In February, the University College of London reported that the global levy proposal had majority support across a “diverse coalition”: African participants, small island developing states, least developed countries, and developed economies actively participating in the IMO debate. Much of this support is based on the “just and equitable” element of the levy plan, where financial support will be directed towards decarbonization efforts in the smaller and least-developed maritime nations.

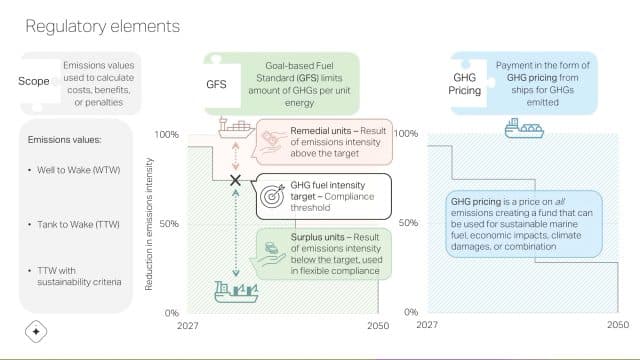

Click to enlarge. Regulatory elements under discussion at MEPC 83. Source: Maersk McKinney Møller Centre for Zero Carbon Shipping.

The global collection of a levy per ton of GHG emissions into a centralized fund is broadly-agreed on point – but discussions around revenue distribution remain unresolved. How exactly funds will “reward the production and uptake of zero and near-zero emission (ZNZ) fuels, whilst also providing billions of US dollars annually to support the maritime GHG reduction efforts of developing countries” is still being negotiated, and the International Chamber of Shipping warns that concerns must be addressed in a “simple and pragmatic way” to build consensus.

While many developed economies support the levy proposal, most European countries back the adoption of a FuelEU Maritime-type scheme at the international level. FuelEU Maritime targets all vessels above 5,000 gross tonnage calling at European ports, mandating GHG reductions in energy used on board. Beginning with a 2% reduction this year, by 2050 all such vessels will need to achieve an 80% reduction.

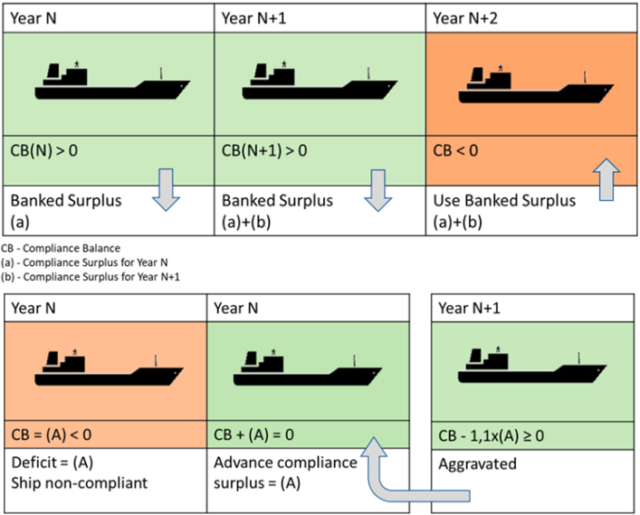

Click to enlarge. The FuelEU scheme will allow a ship to bank or borrow compliance deficits/surpluses. Source: EU Commission.

Crucial regulatory mechanisms included in FuelEU Maritime – namely banking, borrowing, and pooling – will allow shipowners to claim the “surplus” savings from one vessel across pools of vessels, or for a single vessel to make up for not meeting its goals by overperforming in the next reporting period. A few alternatively-fueled vessels may thus be able to achieve the FuelEU Maritime goals of an entire fleet, encouraging shipowners to deploy these new technologies, secure a certified bunker fuel supply, and operate – if only in a limited way to begin with (ammonia-fueled ammonia carriers will be prominent here). This allows alternative maritime fuels to scale based on successful early vessels, and for fuel supply chains to be established. The penalties for not meeting reductions targets are steep, and applied across a shipowner’s entire fleet, encouraging compliance.

But while a FuelEU Maritime-type scheme has the support of most Europeans and some other developed economies at the IMO, there is limited “just and equitable” consideration in this proposal. Rather, it focuses on strict compliance from shipowners, with steep penalties for non-conformance and no additional support for broader decarbonization. For this last reason (and others), smaller and least-developed maritime nations have likely opted to support the global levy and disbursement proposal.

The fuel lifecycle question

There is also the question here of lifecycle boundaries: if fuel needs to be decarbonised, how can we ensure its lifetime emissions are low enough to make an impact?

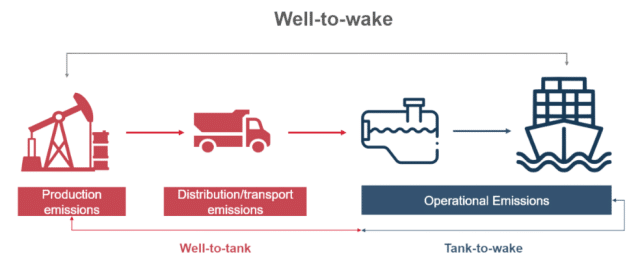

Click to enlarge. Different boundaries for fuel lifecycle emissions. Source: Safety4Sea.

To be discussed at the MEPC 83 in April, the issue over where to draw boundaries for fuel lifetime emissions is a critical one for the IMO. A “tank-to-wake” methodology is currently used in shipping, meaning fuel production emissions are totally ignored. This approach does not include the potential emissions reductions achieved in the production of e-fuels, and it does not include the emissions inherent in for example LNG production, such as methane leakages during extraction. For this reason, the AEA and other groups have long advocated for the adoption of a “well-to-wake” methodology for fuel lifecycles.

Two-stroke engines: full ahead

Click to learn more. WinGD has about 30 orders of its X-DF-A ammonia-powered engines which are set to be delivered for the first time in June. Source: WinGD.

Finally, ammonia-capable engines will become commercially available in 2025. WinGD’s X-DF-A dual-fuel engine is on track for delivery to South Korean shipyards this June, where it will be installed aboard Exmar’s ordered mid-sized gas carriers. MAN Energy Solutions has announced full-scale testing has begun at its Copenhagen laboratory, and Mitsui E&S (a MAN engine tech licensee) has commenced large-bore engine testing in Japan. MAN’s two-stroke engine offering is on track to be commercially available by the end of 2026. Additionally – in the 4-stroke maritime range – Wärtsilä’s 25 ammonia engine will be installed for the first time in 2025 as part of the Viking Energy retrofit project.

The decisions made in 2025 will set the course for ammonia’s role in maritime decarbonization. While the development of ammonia-capable engines is a major step forward, regulatory clarity is essential to ensure their widespread adoption. The industry is at a crossroads, with competing approaches to GHG reduction — whether through a global levy or a FuelEU Maritime-style framework — shaping the financial and operational incentives for alternative fuels. At the same time, addressing lifecycle emissions accounting and finalizing safety and training standards will be crucial to unlocking ammonia’s potential. The momentum is there, but the right policy decisions must follow to translate technological progress into real-world impact.