Hydrogen Council – new global initiative launched at Davos

By Trevor Brown on January 20, 2017

This week, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, the leaders of 13 global companies, representing more than EUR 1 trillion in annual revenues, announced the launch of the Hydrogen Council.

This new global initiative is important for obvious reasons: it presents a compelling “united vision and long-term ambition” for hydrogen, it promises global engagement with “key stakeholders such as policy makers, business and hydrogen players, international agencies and civil society,” and it pledges financial commitments to RD&D totaling EUR 10 billion over the next five years.

It is important for a subtler reason too: it is the first hydrogen industry promotion I’ve seen that includes ammonia. It includes ammonia both implicitly, encompassing “hydrogen and its compounds,” and explicitly, listing ammonia as a “renewable fuel.”

As such, it marks another step towards acceptance of ammonia as an energy carrier.

In previous years, ammonia energy proponents experienced high levels of institutional and industrial resistance. Recently, however, it appears that ammonia energy may be entering a period of recognition and requisition.

In just the last few years, the Japanese government launched the Energy Carriers SIP, and the US Department of Energy began funding a series of ammonia energy projects through ARPA-E’s REFUEL program. Many other funding programs and development projects are underway around the world.

In fact, one of the first recent funders of ammonia energy was the EU, which began funding The Powercube (ammonia fuel cell power generation for remote telecommunication masts, in Africa) in 2010 and, this week, announced another EUR 116 million in funding for fuel cell and hydrogen technologies under its Hydrogen 2020 program.

The Hydrogen Council report defines its purview to include “hydrogen or its compounds,” which it sees as essential technologies to provide “a centralized or decentralized source of primary or backup power,” and to act as energy carriers that “have a high energy density and are easily transported … to (re)distribute energy effectively and flexibly.”

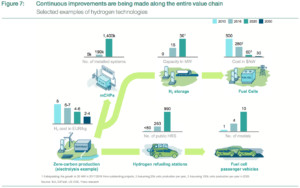

So far, the Hydrogen Council has published one press release and one report. The report, entitled “How Hydrogen empowers the energy transition,” makes the case for hydrogen and ammonia in the transition to carbon-free energy.

As the report makes clear, hydrogen (and ammonia) will play a vital role in the global transition to low-carbon energy because it can:

- “Enable large-scale, efficient renewable energy integration,” due to its ability “to provide back-up power during power deficits or … [be] used in other sectors such as transport, industry or residential” or as a “seasonal storage medium,”

- “Distribute energy across sectors and regions,” as we’ve recently written about, regarding carbon-free energy imports to Japan and to Germany,

- “Act as a buffer to increase system resilience,” as we’ve written about regarding power generation in The Netherlands,

- “Decarbonize transport,” which is the focus of the US’s REFUEL program,

- “Decarbonize industry energy use,”

- “Serve as feedstock using captured carbon,” and

- “Help decarbonize building heating.”

Hydrogen Council member companies include Air Liquide, Alstom, Anglo American, BMW GROUP, Daimler, ENGIE, Honda, Hyundai Motor, Kawasaki, Royal Dutch Shell, The Linde Group, Total, and Toyota.

This is an impressive starting list, representing industrial gas producers, energy traders and suppliers, engineering companies, and vehicle manufacturers. But while their combined investment pledge of EUR 10 billion is a good start, I feel obligated to point out that it is nowhere near good enough. As the report states:

With COP21, 195 countries adopted the first universal, legally binding global climate deal. It aims to keep “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C.”

These goals are ambitious, and current efforts are not enough. The country plans laid out in COP21 … are insufficient. They will increase the average global temperature well above the 2°C mark by 2100. Limiting global warming to 2°C will allow a cumulated emission of energy-related carbon emissions of approximately 900 Gt of CO2 by 2100. At current annual energy-related CO2 emissions of 34 Gt, that ceiling will be reached before 2050.

Hydrogen Council, How Hydrogen empowers the energy transition

While the Hydrogen Council is certainly part of a rising tide of ammonia energy-aware initiatives, its proposed EUR 10 billion RD&D investment is but a drop in the ocean. For a more forceful investment argument, read Bill McKibben’s recent article in The New Republic.